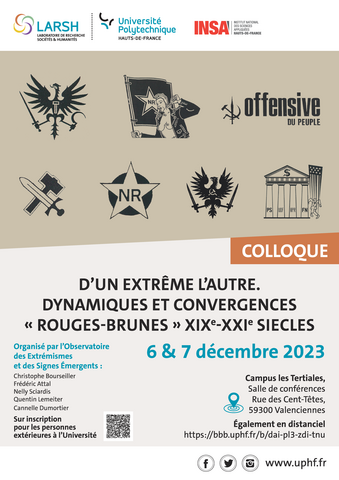

Colloquium: D'un extrême l'autre. Red-brown" dynamics and convergences XIXth-XXIst centuries

Organized by the Observatoire des Extrémismes et des Signes Émergents

In 2014, ethnologist Jean-Loup Amselle published an essay entitled Les Nouveaux Rouges-Bruns. Le racisme qui vient (Éditions Lignes) where, using the metaphor of political colors, he analyzed the phenomenon of defectors from the far left to the far right in the name of a common ideological melting pot " primitiviste " in which concepts such as autochtonie, peuple, communauté, nation, popular culture... were found. The first occurrence of the substantive adjective " Rouges-Bruns " is however older, dating back to 1993 following a provocative article published in L'Idiot international (Jean-Edern Hallier) and written by former Gauche prolétarienne Jean-Paul Cruse, entitled " Vers un Front national ". The " temptation national-communiste " (Olivier Biffaud, Edwy Plenel, Le Monde, June 26, 1993) is said to have arisen shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the outbreak of conflict in the former Yugoslavia. The context in which the Maastricht Treaty was approved should also be remembered. Former Stalinists, nostalgics of the Soviet Empire and far-right ideologues (Alain de Benoist) came together to denounce globalization, US imperialism, Zionism, " anti-racist racism " and celebrate the Nation and the Eurasian Union.

This would revive the " national-Bolsheviks " whose appellation goes back to the singular trajectory of Ernst Niekisch (1889-1967) who passed from the SPD to the uncompromising defense of the State and the Nation, spearheaded by the proletariat. As early as 1919, a number of political nebulas began to appear in Germany, combining social and racial demands. A " national-bolshevik " current (Hamburg) joined the KAPD, which quickly excluded it (1920). Fascist Italy offers other famous examples, not limited to Mussolini. The thirties saw a proliferation of crossings from extreme left to extreme right, some studied individually (Doriot...) and others more collectively (Gilbert Merlio (dir), Ni Droite ni Gauche. Les chassés-croisés idéologiques des intellectuels français et allemands dans l'Entre-deux-guerres ", MSH d'Aquitaine, 1995). And from the Fifties to the present day, other far-left figures have joined the other extreme.

The phenomenon is therefore a long-term one, and raises questions for historians, historians and political scientists, among others.

The shift from far-left to far-right is not unique to the 20th century, and post-revolutionary France offers similar cases (Henri Rochefort from the Paris Commune to Boulangisme, to take just one example), which it will be important to revisit. While trajectories from the extreme left to the extreme right are numerous, the opposite is also true in the Europe of the 1970s, a particularly rich case study. Are these individual or collective moves? How are they justified by these actors ? Are they conversions, tactical rapprochements or convergences? What part does the political, economic and social context, opportunism or ideology play in these possible convergences ? Where do anti-Americanism, anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism, racist nationalism, neo-paganism, anti-industrialism fit in? What are the effects of the transfer of political figures and intellectuals from one camp to the other on voters, certain social categories and society in general? The shift from one extreme to the other raises the question of radicalization, but should not obscure a possible process of de-radicalization.

So many questions and problems that call for research throughout the contemporary era and the present day, in Europe, the United States but also in other parts of the world affected by the phenomenon.